Strasbourg, November 1793. BAD WEATHER FOR THE BAKERY!

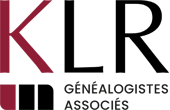

Following on from the financial crisis of 1789, France plunged into a serious frum crisis. From 1791, a year of poor harvests, until the spring of 1793, the country was shaken by countless subsistence riots, often severely repressed. Inflation soared, exacerbated by the collapse of the assignat, which lost 40% of its face value in the summer of 1792. It’s a blessed time for agioteurs and profiteers of all stripes.

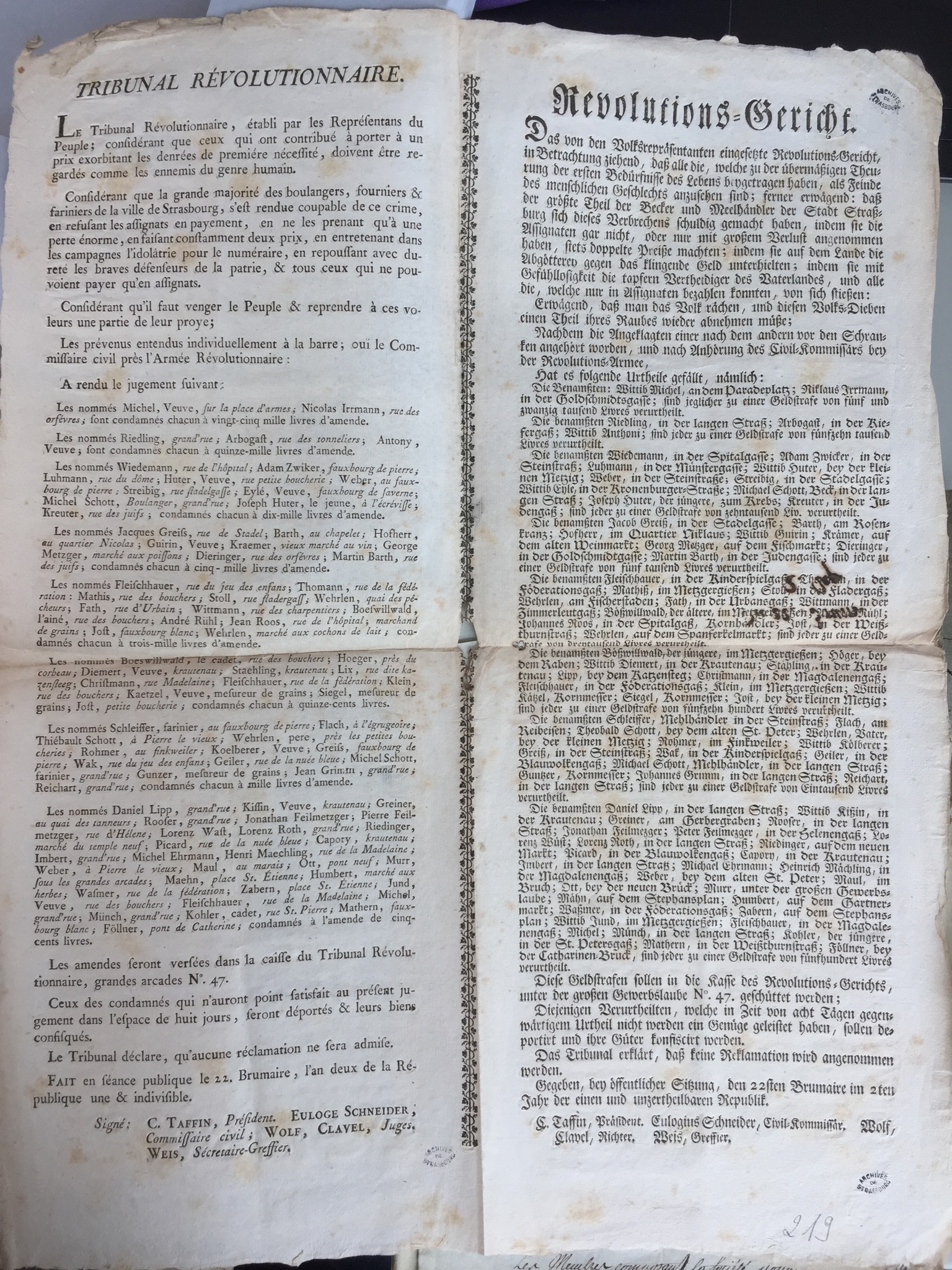

On November 12, 1793, the Strasbourg Revolutionary Court severely criticized the bakery guild. Accused of having “contributed to the exorbitant cost of basic necessities”, bakers and their ilk are to be considered “the enemies of mankind”, no less! The profession “has been guilty of this crime, by refusing to accept assignats in payment, by only taking them at a huge loss, by constantly charging two prices, by fostering idolatry for cash in the countryside, by harshly rejecting the brave defenders of the fatherland & all those who could only pay in assignats.” Between the lines, they are reproached above all for having sniffed out the misappropriation of scrip very early on and, like the farmers, demanded to be paid in cash, to the great displeasure of an exsanguinated population.

The aim is to “avenge the People & take back from these thieves a part of their prey”. The sans-culottes don’t mess around. After a quick trial, exorbitant fines ranging from 500 to 25,000 pounds were levied. For the young Republican municipality, this is an unhoped-for opportunity to replenish its coffers and finance its direct support for the grumbling population. The court declares “that no claims will be admitted” and, without payment into the Revolutionary Court’s coffers within eight days (in hard cash, not in depreciated assignats), the condemned “will be deported & their property confiscated.”

This document, printed in French and German, provides a good snapshot of the city’s bakery supply in November 1793. The “vast majority of bakers, bakeries & flour-makers in the city of Strasbourg” – 82 craftsmen and a few grain merchants and scorers – were thus thrown into public disrepute. Strasbourg was home to 47,254 people in 1793, so there was at least one bakery for every 600 inhabitants, a figure to be compared with our current figures: in 2020, 400 bakeries (including 130 in Strasbourg) were operating in the Bas-Rhin region, i.e. one establishment for every 2,872 inhabitants – bearing in mind, however, that bakers now produce only 60% of total bread consumption.

In 1793, it was not difficult to find bread in Strasbourg outside periods of food crisis. A string of 11 bakeries then graces the Grand Rue with the smell of warm bread! Some streets have 4 establishments (rue de la Madeleine, Krutenau), others three (Faubourg blanc, Faubourg de Saverne, rue de la Petite boucherie, rue de la Fédération). Seven streets or squares have two. Of course, the relationship with bread was not at all the same as it is today. In the 18th century, daily consumption per person was close to one kilo, a figure that had barely changed by 1900 (900 grams). The decline was then rapid and steady: a French person in 1950 consumed 325g a day, compared with 120g today. The reasons for this inexorable decline are another story…

Sources :

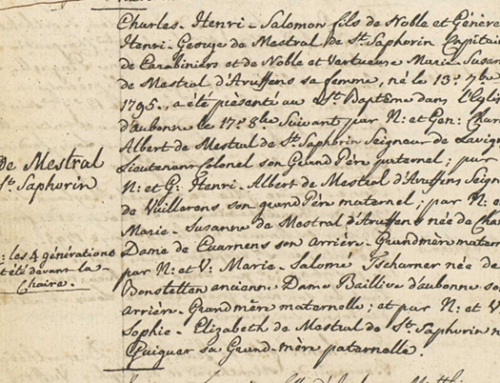

. Archives Municipales de Strasbourg, Fond des Jacobins, Société des Amis de la Constitution, 205 MW 9 (142-257)

. Archives Départementales du Val d’Oise, 1 LU SUP 32

. Website of the Confédération Nationale de la Boulangerie et Boulangerie-Pâtisserie Française, https://boulangerie.org/economie/

. Strasbourg demographics” Wikipedia page, https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/D%C3%A9mographie_de_Strasbourg

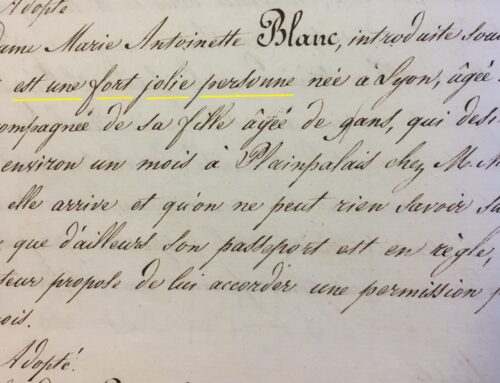

Illustration: forged assignat of 1000 livres, An II.

Leave A Comment